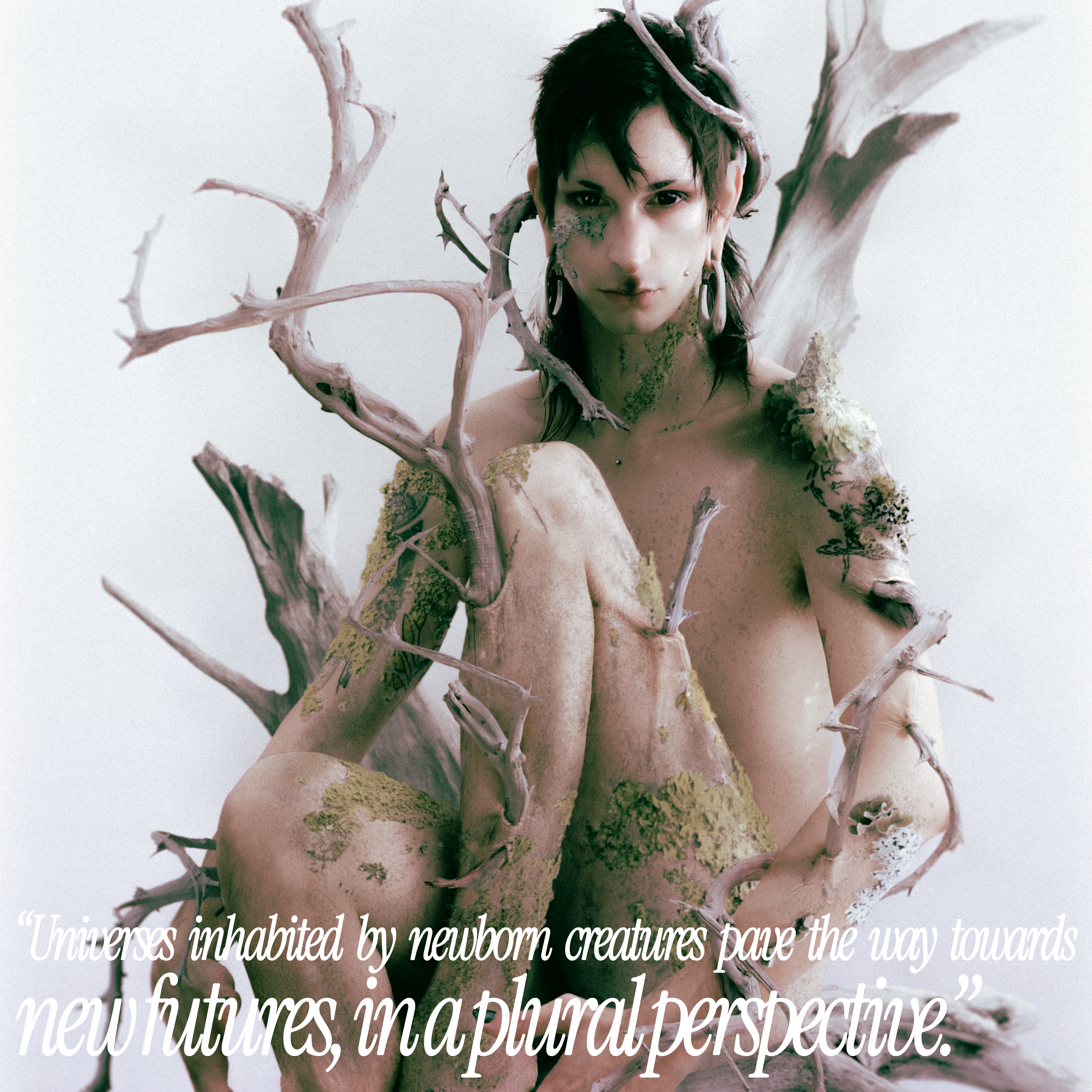

B. Filippo Chilelli

Universes inhabited by newborn creatures, that challenge the structures of the present and pave the way towards new futures, in a plural perspective.

Marte Gastaldello: Your research takes us on an exploration of the connections between identity and shape, giving birth to organisms that exist in a hybrid state between Human, Natural and animal. With a multimedia practice, you give life to creatures and universes that undermine the structures of our present.

B. Filippo Chilelli: The great transformations in humanity and in the world that we have seen in the last decades have led to a radical change of the threshold between what is Human, artificial, cultural and what is Nature. We, as subjects, are constantly in the making, transforming ourselves. My research is an ode to bodies that don’t forget this principle, and consciously mutate and hybridize. My work is dedicated to the alliances that make us look into a new kind of future, balancing the combination of phenomena, thoughts and identity in the present. In order to survive, I think it’s necessary to imagine new ways of living. What happens when the enhanced human is combined with the other-from-itself? What figures, identities and narratives can emerge from such alliances? What sceneries and contemporary debates do they cross?

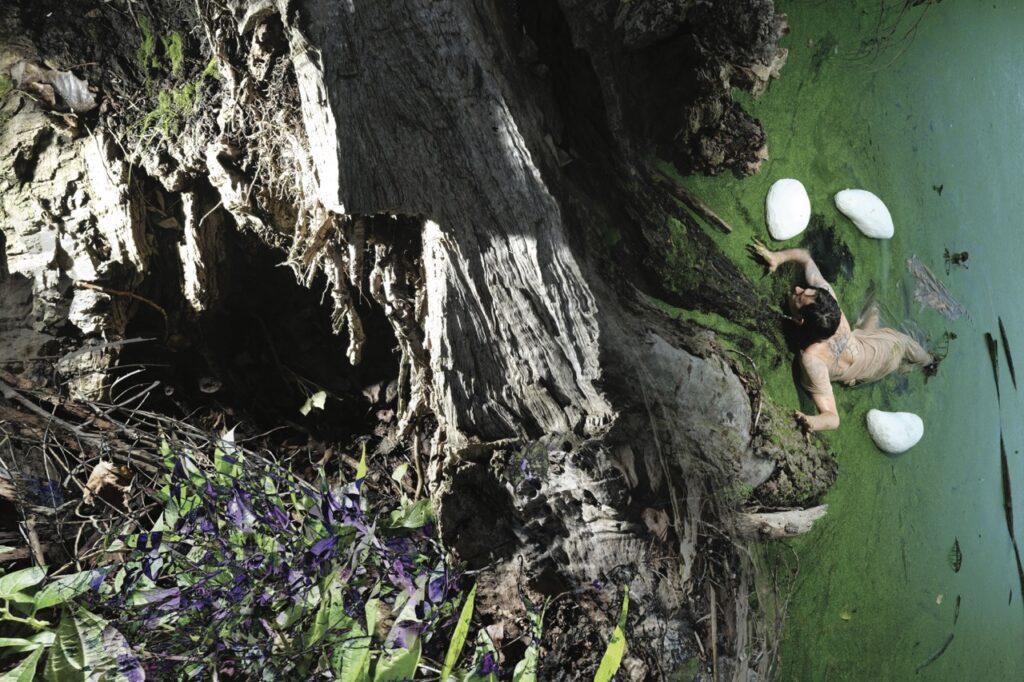

Universes inhabited by newborn creatures, that challenge the structures of the present and pave the way towards new futures, in a plural perspective. From organic to inorganic, from human to insect, from individual to multiple: matter is altered multiple times while it’s searching for its final shape. Moving across practises of coexistence, care and imagination, the works inhabit a liminal space between life and death.

This is where the genesis of uncharted alliances takes shape.

MG: I feel like it is crucial for you to sculpt using existing organic elements, materials and substances. At the same time, though, you are always able to alter their initial shapes to some others you feel are more fit. What happens to your creatures when they are transformed? Would you say that it is transforming you too?

FC: My artistic career started with painting, but even since my first two-dimensional works the materials I used took me far away from a traditional approach. What was crucial for me was the discovery of materials that, by changing the surface, were adding layers to the work and making my research more similar to what happens in reality.

This kind of curiosity blossomed when I started working on sculptures. When I’m sculpting, I am not only depicting a situation or a body. I am shaping it. It becomes a gestation, a process in which chemistry plays a huge role, in which materials become hidden parts or visible elements and they change constantly. Sometimes also by giving unexpected results. We are a manifestation of our complexity and continuous transformations and it’s important that my works include this aspect.

MG: Your sculpted organisms are often contained in shells of resin. What does this process mean to you? Are you searching for some kind of protection?

FC: I’ve always been inspired by the Wunderkammer (“Chamber of Wonders”), in which intellectuals used to collect their scientific curiosities. My room as a teenager looked like the studio of a traveler who had many memories and found objects from adventures that never actually happened. Growing up, I came into contact with many underground worlds that were politically active on matters of gender, race and class.

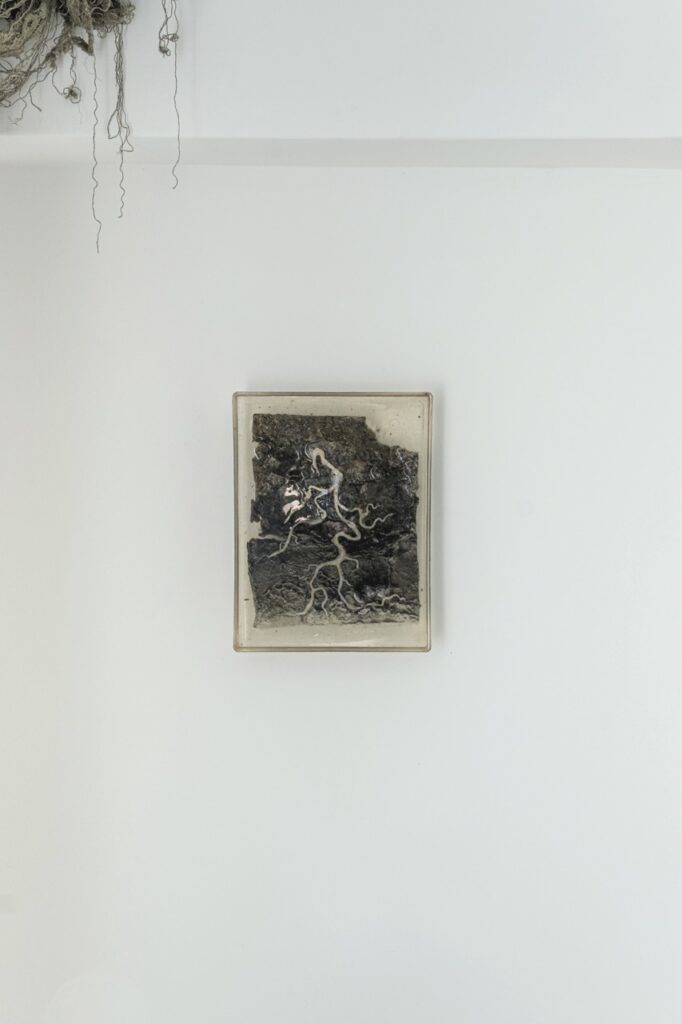

Being a Non Binary person myself, I’ve learned the importance of having a net of support and community, but also the importance of having quiet moments of tranquility that I can use to take care of my needs and manifest them in growth processes. Since we are always changing, we also need a space in which we can turn inward, making a sense of all that’s happening. We need liminal mental spaces in which we can contemplate our complexity without the chaos typical of the external word. My first resin works were born from this: natural imbalance, community care, moments of transformation, a closure that generates a new opening. How much transformative power is there hidden in a chrysalis that contains an egg hard as a crystal? Would you expect a centuries old flower to bloom now? In order to survive we also need the right moments of protection.

MG: I want to take some time to talk about one of your latest installations, Kin Omnia. I feel like resin is there to suggest that the creatures contained within it would be vulnerable if they were to be left on their own. At the same time, their strength is expressed by the connections they form with each other on the floor. And the title of the piece itself contains the word “kin”. What does family mean to you?

FC: Kin Omnia is dedicated to the profound connections made during the growth processes of vulnerable creatures. It’s made of seven chrysalises contained in resin eggs, linked to each other by an environmental connection that’s reminiscent of natural structures of fungi, aerial visions and synapsis. Their strength manifests itself in this connection.

Making “kin”, as taken from Donna Haraway’s research, means having a profound faith in unexpected alliances. It refers to any type of bond, multi-shape and multi-species, that ties subjects in a care process, through inventive connections, outside the genetic component. Making “Kin” in our time means creating disorder, mixing narratives and giving possibilities to hope and unexplored relations.

As queer people, we are aware of the importance of creating such spaces to live better, together. A queer family is first of all a safe space: what brings us together is the creation of a place and time for long-term care, as well as being part of a support system that offers different types of answers. It goes beyond the concept of friendship or romantic affection. It’s more about finding yourself reflected in someone else’s experience; building and walking your own path, but together.

MG: Is there an animal or natural process that you feel like we definitely have something to learn from?

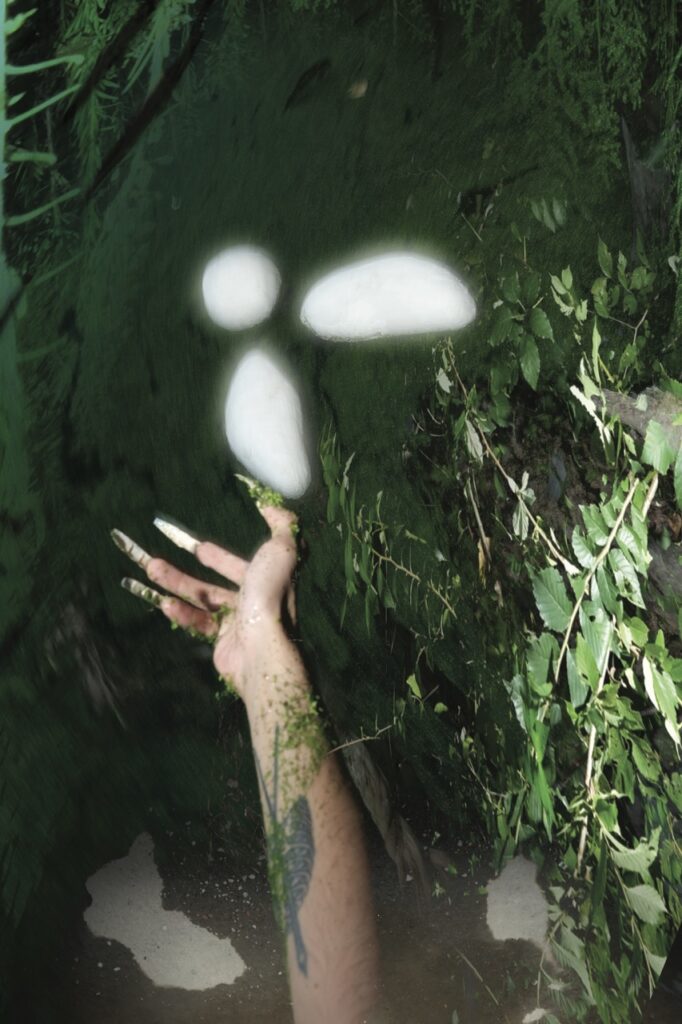

If you think about practices of solidarity, justice and care, we have so much to learn from the worlds around us. First of all, we should aim at living and dying at peace with each other and not being scared of contaminations. I use the word “hybrid” very often as it is something that fascinates me, but it reminds me too much of taking two things and mixing them. More than hybridization, I think that what we need is an implosion, an emerging of something different, sometimes possible in other worlds – worlds that actually have always been here.

I’ve recently made this sculpture called “HYPHA”, inspired by the connections of fungi that make it possible for surface vegetative individuals to live under the soil. I love how it becomes a silent communication channel, necessary for the functioning of a bigger scene.

Our morphology and language influence the way we see the world. For example, the way spiders or octopuses are built makes them move in every direction, not only in a straight line, which for us would be the logical way. At the same time, they can stretch their legs and tentacles in order to feel the environment. The Portuguese man o’war is a perfect example of cooperation and interconnection.

Siphonophora are another amazing example, as they gave up individualism in favor of a symbiotic network. In this colony of octopuses cooperation originates from a manifold creature, tentacular and disembodied, in which each creature has a specific role in helping the others. I believe that plural bodies and bodies in cooperation will indeed save us.

Donna Haraway speaks of “sympoiesis” and not symbiosis, because, while symbiosis is a relation with a specific aim, sympoiesis implies co-creation, living-with, becoming-with, creating-with. I think that many creatures in the world behave in a queer way: they don’t have a fixed identity or shape. They thrive on connectivity and sympoiesis.

MG: Kin Omnia is your first work installed in a space after your personal exhibition at Macao, Sopra Sotto. An exhibition in which the majority of the work were paintings, and even when you created physical structures, they still carried a pictorial propriety. Looking at it now, do you feel that your practice has changed since that exhibition?

FC: “SOPRASOTTO” was born in the MACAO basement, with the intention of redeveloping an abandoned space, in the hope of returning the building to cultural value that seemed long forgotten. The result was a metamorphosis of a place that did not exist, showing itself to be coherent in content and in dialogue with the works.

Before its closing, Macao was a free sub-cultural space in Milan. I remember that, after my solo show, I wanted to transform that abandoned space into a free open studio to make and see art in the underground, free for all the young artists who are suffering from the high cost of living in Milan. It was the lockdown years and my practice was very linked to politics. Maybe in that time creating a community moment was more important than the theory behind the works. We all needed to claim a space and time that made sense of us. Which is why Soprasotto has become like a church for prayers and rage. Now my work has found a home, a sense of belonging that feels more immaterial, a kind of balance. Maybe I found that too.

MG: Your paintings are depicting forms that are visually reminiscent of rituals and sacred objects. I do feel that this installation emerged in a constant dialogue with the place you occupied. What do the elements you generated say about the nature of the exhibition?

FC: In 2019, my research materials were microorganisms, marine creatures, circulatory systems, satellite visions: bodies that we know, but which seem to us always unknown at first sight, from another planet, far from us.

The visual correspondence between an atom and an aerial vision – as it is photographed by a satellite – shows how the natural world has always had its laws on material construction. But, in order to link shapes such distant from each other we need a kind of formal synthesis.

So, the bodies in my works become alien landscapes to explore.

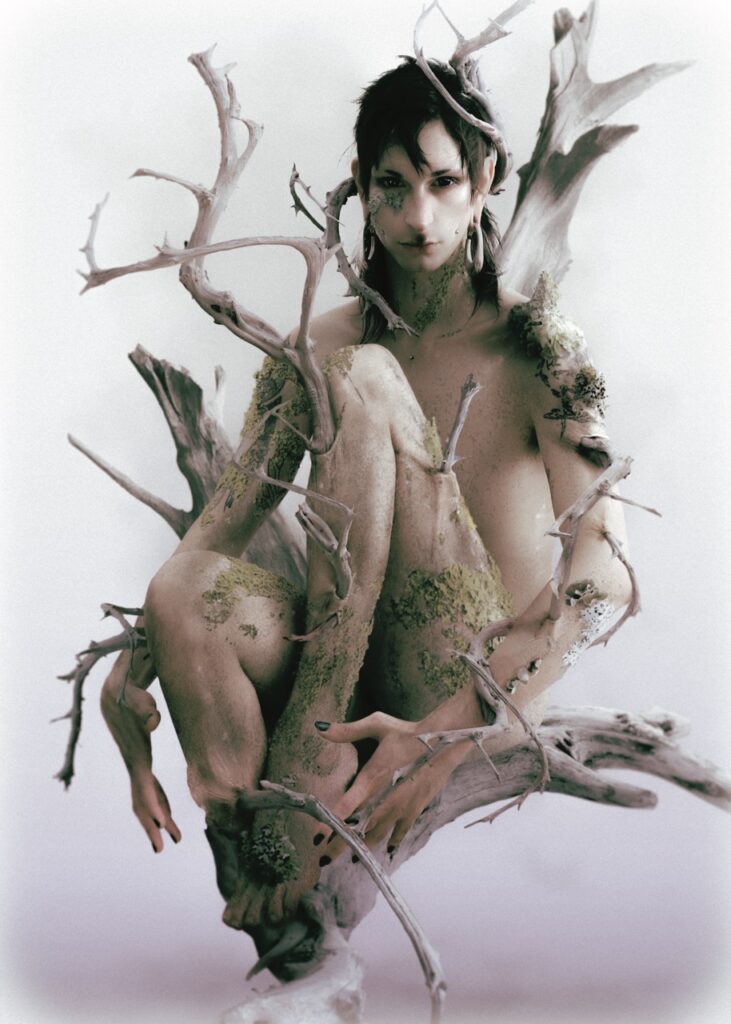

“VENERI” (venus) and “GOLEM” are the two totems of the exhibition, two large pictorial works that show bodies made of branches, rivers, veins. They are a landscape, they are a human body still in gestation, they are corpses, they are Goddesses to pray while you dance tekno music around them.

Practices of aggregation and praying are archaic and primordial, rituals that need their own totems. Such objects bring many to connect over a sense of freedom that right now, in the present world, is very much other capitalistic control. The rave/free party movements is a perfect example of a plural, self-managed body, who moves in the underground to give life to a new form of freedom.

MG: You gradually have come closer to your own concept of body, that is trying to hide its shape by subtracting instead of adding elements to it.

FC: We as a society are extremely linked to images. We need specific symbols to move towards a more inclusive representation, something that can bring back histories and individualities that have been previously erased. Telling the stories of Trans* People now has an immense power over the awareness of new generations. Today it’s full of archives that give a voice to a previously erased past. There’s been a huge amount of re-claiming.

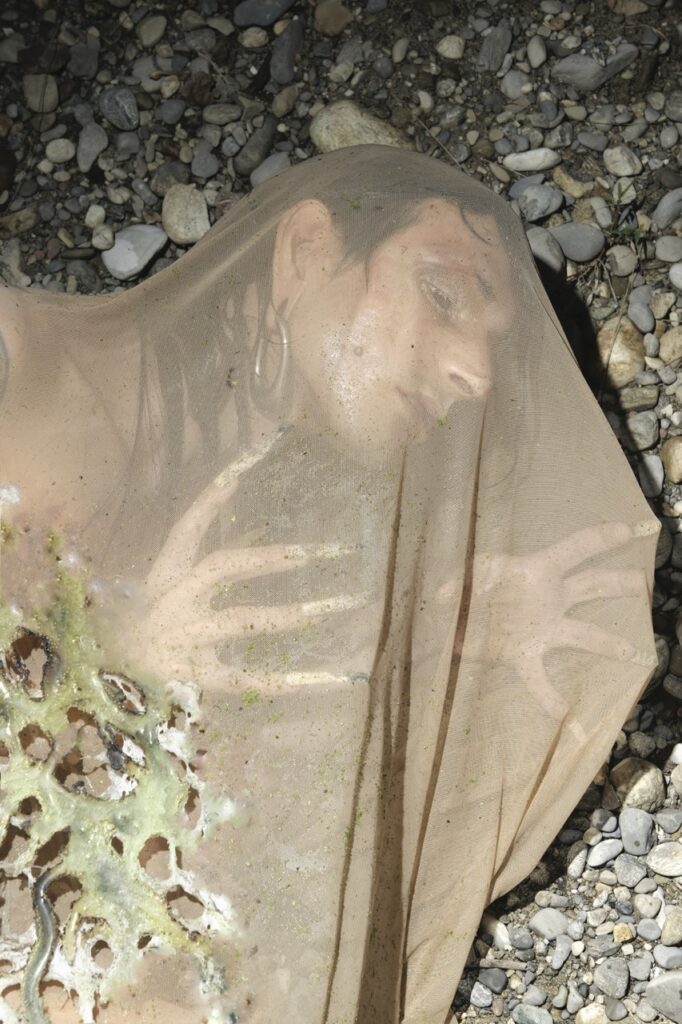

Paradoxically, I want my work to move in a direction that goes way beyond humans. In these years I’ve often asked myself how to represent bodies and what kind of bodies I was talking about. The answer I gradually have to myself is: a symbolic body that has faith in contamination, that, by opening itself to an external space, so far away from everything, becomes extremely thin and universal, travels through different realities at the fastest speed and absorbs as many stories as possible. This is what I meant before when I was talking about synthesis. We all are present in those symbolic environments made of veins. My body dysmorphia is very linked to the cultural aspects of being an AMAB person, even though I don’t feel the need to start HRT. I appreciate my body as long as it doesn’t have societal and cultural expectations that impose a specific performativity on it. Which is why in my works and performances, the body often becomes an universal body, stripped bare of specifications and characteristics. I want to be as immaterial as I can.

MG: In her essay “My words to victor frankenstein above the village of Chamounix”, Susan Stryker uses her rage as a Trans* person to build a community of new subjectivities that carry a transformative power. It all begins with an analysis of the figure of the monster, something that goes beyond gender and represents the power of a new, queer, post-human Trans* body. This idea of reshaping potential and community is something very present in your artworks as well. Did you have some creatures to inspire you like it was for Stryker? Can Mary Shelley’s monster still be used to describe our situation or has it been surpassed by something more accurate?

FC: By declaring herself as “non-human material”, Susan Stryker begins her reflection with the etymology of the word “Monster”. “Monster” comes from the latin Monstrum, “divine prodigy”, formed from the root of the verb “monere”, to warn. Just like angels, Monsters were messengers and heralds of the extraordinary. They announced the approaching of a revelation, saying basically “Be careful: something really important is about to happen”. Being queer, Non Binary, intersex, is being monsters: messengers of other possible worlds.

The gender issue is very similar to the way technosciences make it possible for us to transform our bodies. They are both very human practices of transformation and rebellion, where rage is sacred and community is a safe space in which we can exercise our freedom. Through them, we become a plural body that, through a movement that goes from the inside to the outside, embraces all the people that are part of that individual’s intimate life.

Being monsters is about courage and identity freedom. Our common enemy is the norm, a future already written for us that we don’t belong in. We need other stories of other practices that, as I said, are already around us. In this I feel very inspired by the neo-materialist and eco-feminist thought. For example, Donna Hararway makes a comparison between the becoming of spider webs and the becoming of Trans bodies. Haraway imagines a sort of “aracnosexuality” of the trans body as a textural body, that emerges from its own viscosity, until it becomes impossible to tell what’s outside and inside. Or to separate humans from non-human animals.

The heralds of a different future are the inhabitants of the Earth, that we should observe and respect for our own survival.

MG: How do you relate continuous transformation of the body to resin, a material that stops in time what’s put inside of it?

FC: If you think about it, the stories that my works tell are stories of every time. They are contemporary just because now we have this desire of re-discovering, re-narrating things through a kind of justice that’s feminist, social and ecological. Probably also because of the internet, our generation is the first that doesn’t learn from the previous one. There has been a very clear shifting of paradigm. We are now active observers, but we live in a sense of frustration because we have no agency over our present. Future is not waiting for us anymore, we have to fight for it, maybe that’s why today many artists are imagining an imaginary future. We want transformation.

Our care practice begins with finding values, times and places that belong to us. In my works I invoke the strength of a transformation inside the body and an external, protective force. Such powers and divinities are something that belong to any time frame. My suggestion is one of a primordial body that belongs to a remote past or a far future, that comes to us thanks to our ability of conservation and collective care.

Resin becomes then the shell that can save it from the forgotten, and give it the necessary strength. We can be plural and immaterial bodies, but we also need a reality around us that protects us, that is strong like a crystal.

MG: I feel like your practice is growing even more towards new interpretations of the same natural materials you used for Kinomnia. What can you tell us about the new work?

FC: In Kin Omnia every element was dialoguing with each other. In my new sculptures bodies are plural and multiform, an embrace of transformation between more material beings. What since now has been interior becomes exterior and what before horizontal now becomes vertical.

However, there is still a primordial presence that governs the birth of my works. Every component is tied to the other by vital, symbiotic functions. Their roles are however very far from humans’ patriarchal vision.

If the resin before only meant protection, now in “Cicada” elements of resin become the new, something that is coming out of a bigger maternal body that offers protection.

“Arborea”, “Serafini” and “Bones and Flower” are large-scale sculptures made of organic and inorganic materials that merge with each other and create bodies rising from above. “Arborea” is a resin chrysalis that contains an ecosystem fixed in time, “Serafini” is inspired by an embrace of two multi-shaped messengers. Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones are, according to the old testament, of human appearance but they also have multiple faces, many wings or animal parts, representing actually a post-human concept. Their presence was indicating the highest divine manifestation, as angels belonged to the highest celestial hierarchies.

I imagine this new cycle as birthed by the same maternal entity, that manifests itself in different forms and generates different apparatuses. Shape finds its habitat in the exhibition space, transforming it into a secret garden for the monster’s future promises.

DEVONIAN MATER;

B. Filippo Chilelli in conversation with Marte Gastaldello

Photography by Lars Larkin @larsk.larkin

Art Direction Stena Brogna @stenabrogna

Set Design by B. Filippo Chilelli @phil.cosmo

Post Production by Stena Brogna, B. Filippo Chilelli, Francesco Saverio Tani @_thanyyyyyy

Assistant Diego BPTSM @bptsm